Personality

Brussels mag N°17

Dossier

TEXT Johan-Frédérik Hel Guedj

What will Brussels become? We have invited several leading players to give their views on the subject. “Towns are recognised by their reasoning, just like people”, wrote Robert Musil in L’Homme sans qualités. He was talking about Vienna (top of the list of capital cities where life is beautiful). Will Brussels be inspired by this example? To enlighten us about what Brussels will be like in the future, some Brussels protagonists, sometimes severe, often benevolent, share their vision with us.

According to the youngest of these experts, Simon Brunfaut, philosophy professor at ESA St-Luc and lecturer at the École Supérieure des Arts, “Brussels is chaos, but it survives. The varied architecture has its charm, compared with the rigueur of the Haussmann style, a participle of damaged urban landscape and the prickly mobility that we experience, a result of thoughtless choices. What is born from this chaos does not exclude something new”. In his eyes, the ensemble of the European institutions, formless and not at all integrated with the city, is emblematic of these ‘choices made for lack of anything better’. The singer Arno lauds the disconnected Belgian surrealism, and Brussels is an illustration of this. Another singer, Kris Dane, born in Antwerp but living in Brussels since 1998, appreciates “the diversity of languages in this town which belongs to no one and everyone”. In Flanders, the majority group is Flemish; in Wallonia, Walloon; Brussels is apart. He views Brussels as if it were the New World, with its Irish, Norwegians, Italians … and its Belgians. He thinks it is essential to organise the 19 communes in an overall vision in order that the political families stop “arguing who is taking care of their infant, Brussels. The infant is an adult!” Simon Brunfaut agrees with him, “We need for Brussels to be run decisively, a long term vision of the whole which is sadly missing among the mayors of the 19 communes. Just remember the time when the Grand Place was just a car park; finally that came to an end, because people dared to make it so. Antwerp has a mayor who has real powers”. All the major capitals, London, Paris or Berlin, have a mayor. The present mayor seems to be there by default, after the Mayeur scandal. “Aside from the debates on the calamitous mobility or an imaginary looking backwards regarding the Marolles, I expect a vision and proposals.” The first person concerned, Philippe Close, recalls that the capital has 184 different nationalities and that 35% of Brussels inhabitants are not Belgian. Of 35%, 82% are Europeans. If Brussels wants to be ‘adult’, it must fully assume its status as the capital of Europe. He states that the European district is alive: as proof, there is the growth of cafés, terraces and, he smiles, demonstrations: more than a thousand per year, featuring European policy. He is not convinced that an institutional reform would resolve the Brussels equation. “The institutional complexity is the result of the difficulties of our communities to coexist. In this respect, Brussels is a binding agent. The effectiveness of our governance is linked to its proximity. We are closer to the German model than the Parisian model.” If a town is a body the circulation that irrigates it is vital. On the crucial subject of mobility, he reminds us, the region is the pilot for the major urban trunk roads, car parks, public transport and major town planning permits. It would be good to take inspiration from the Flemish STOP principle of the Vervoot III government, the Ghent model which establishes a hierarchy for modes of travel (pedestrians, cyclists, public transport and cars). The governmental agreement for the Brussels region 2019-2024 foresees for 2021, a generalised 30 km/h zone outside the major trunk roads.

Smart cities

Dominique Riquet, who is French, succeeded Jean-Louis Borloo as the mayor of Valenciennes, a town that both mayors have significantly modified. Member of the European Parliament, a parliamentary specialist for transport, he is astonished by the way Brussels manages its public space, particularly the road works and traffic. “A management committee brings together the underlings but not the executive. This division of the governance prevents the responsibilities from being clearly established. The result of this is a lack of maintenance. Let us take, for example, the famous tunnels: the intra-tunnel roads depend on one entity, the roads above the tunnel depend on another entity and the service lines depend on a third entity. Each entity has observed that as there is a lack of coordination, a tunnel can remain closed for several months before any real works are started. In addition, there is the lack of funds: contracts are drawn up with limited budgetary allocations, per phase, which slows down the completion. Ordinarily, a town restricts the impact on the flow of traffic by closing roads in one direction only, managing the inter-communal alternative routes and calls upon the police to regulate the traffic at sensitive points. The Brussels traffic system concentrates a mass of commuters in the European district. Aberration: the tramways are rarely in the right place, which makes them as slow as the cars. Finally, the delivery timetables are inadequately regulated and controlled.” What will remedy this? “The federal, regional and communal entities must absolutely create a single management structure for the public highways that would be the single voice of the contractors.” This is the method of exemplary smart cities, such as Copenhagen or Stockholm, a centralised regulation and a transport inter-modality among underground, bus, bicycles, scooters, etc Finally, if such a management structure had control over the pedestrianized areas, it would completely reverse the situation: “Boulevard Anspach has been pedestrianized, the adjacent streets continue to have traffic which blocks the whole area: conversely, towns that pedestrianize preserve the main road carrying traffic, in this case, Boulevard Anspach, and pedestrianize the adjacent streets”.

A town that is a crossroads

Another significant player with systemic thinking is Roland Cracco, CEO of Interparking, he points out that the density of the capital (7,430 inhabitants per km2) makes it close to London (5,550) and far less than Paris (21,000). This very tolerable density goes hand in hand with a strong geographical position (despite the fact that Brexit runs the risk of moving the centre of Europe towards the east) and a financial wealth that does not reflect the average standard of living (€13,000 per annum). As in a model American town, it is poorer in its centre than at the periphery, notably with a pedestrianized area and fewer car parking spaces, which encourages people to live in the city outskirts. According to him, activity in the town centre must absolutely be recreated by making it active. “A town only develops if it is a crossroads. It must be open to the Flemish people and to the Walloons who want to spend time there. Trains must run later. As for the car, we are moving in the direction of digitized vehicles, car- sharing, electric cars, and eventually, self-drive cars. New technologies will soon optimize parking and traffic flow. This presupposes intelligent infrastructures and a regulation of the ‘air traffic controllers’ model. We are working on more compact parking projects, where the car will be parked automatically: people will no longer have to enter the car park which will be a huge saving in space. In Namur, there is already a filter system which allows us to have air in the car park that is purer than on the outside. This will soon be the case for the car parks located at Deux Portes and the Grand Place.”

Dimitri Jeurissen, associate founder of the Base Design agency has studied the town in relation to the redefinition of the Bourse, which will go hand in hand with the refitting of Actiris, located opposite. “The purpose is to maintain the residential, commercial, cultural and educational balance. The idea is to turn it into a public area around an experience centre devoted to beer and the history of beer, with a restaurant on the roof, all planned for the beginning of 2022.” The goal is that Brussels inhabitants will go to the Bourse as they visit the Galerie de la Reine. From the Bourse, the main road that leads to the canal forms a ‘T’ with the MIMA on the left branch and the future centre for digital and technological art, the iMAL, on the right branch. Another important project is the development of the Tour et Taxis district. “It is also important to maintain the balance among the activities of the town and tourism, having a foothold and passing through.” It is the very essence of a capital city to have several centres, without this originality leading to asphyxiation.

A gentle traffic flow

The architect Pierre Lallemand (see the article featuring him in this issue), points out that no capital in the world receives more heads of state, and yet it does not possess a meeting point between the public space, the administration and the citizen. “It is the European capital of a power without a place to express itself. Without the European Union”, he states, “Brussels would be a dead city. And yet, the European district is sorely in need of a face-lift, which would demand a double burst of energy, Federal and European.” At the summit, the headquarters of major multinationals have succeeded the great families of the epoch of King Leopold. For the rest, Brussels reflects the image of Europe, a continent where the minorities have a power without equal, where so many Europeans contribute their part of the town’s identity. For a long time, the city was made up of business areas (Nord and Léopold), entertainment areas (Kinepolis) and residential areas (Uccle and Woluwe); it is now benefitting from a prosperous immigration which is rendering the town ‘bourgeois’. The market at Place du Châtelain has become polyglot, but is there an exchange between the Brussels ketje and the bourgeois immigrants?

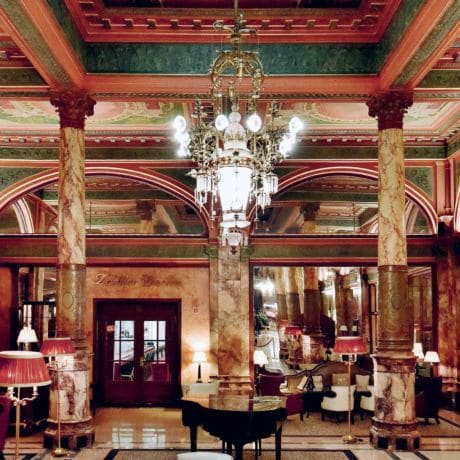

Constantin Chariot, director of the Patinoire Royale, shares this multipolar vision, “Before Léopold II, Brussels was a provincial town confined within its pentagon. Afterwards, it became structured around two cultural areas: the Mont des Arts and Cinquantenaire. One of the future elements for the capital will be to connect these two areas via a gentle flow of traffic. The project being studied by the Parliament will offer a pedestrian flow between Belliard and Loi (another renowned architect, Philippe Samyn, qualifies this as a ‘sewer filled with cars).” Let us go down on the north of Parc Léopold and the garden of the Wiertz Museum, the Maison de l’Histoire de l’Europe, and the Bibliothèque Solvay. Another area is being formed on the north ring that is permeating into Flanders around the port and the Midi station, Place de l’Yser and Tour & Taxis. Major real estate firms are investing here; the site of the UP tower is an indication of this. This ring area is now welcoming a new population: individualists, childless couples, the Boho set (Bohemian and Bourgeois) and ecologists. In contrast to other capitals, Constantin Chariot thinks as Roland Cracco that Brussels will remain a town with different districts and without a hyper-centre. “Brussels was formed by contiguity, increasing by adding one parish after another in the 19th century. This pedigree favours more of a family life than in Paris or New York.” The Palais de Justice will no doubt change its purpose, and the entrance to the Mont des Arts will be a town-planning issue. Finally, in his eyes, there are four typical Brussels tropisms: the cinema, comics, public sculptures and the arts, which will bring about a festival of cinema of international stature, a museum of press cartoons and comic strips, an enhancement of craftsmen’s expertise (featuring the Van der Kelen school) and open air sculptures. Finally, there is the question of what will become of the Abbaye de la Cambre after the departure of the IGN (National Geographical Institute). Chariot sees a lesson in this catalogue, in the style of the French poet Prévert: Brussels does not think of itself as a whole, but as fragments. This is its limitation, and its charm.

“Brussels is the European capital of a power without a place to express itself.”

Personality

Face-à-face

Portrait

She in the plural

1 establishment, 3 trades

Expat

back stage

THE MOST BEAUTIFUL ONES

in the picture

Values

Beautiful racing cars