Dossier

Brussels mag N°18

Graphic art

TEXT TRONG GIA NGUYEN

The graphic arts tradition is long and storied in Belgium. All of us know the iconic characters from our childhood, but a new generation of storytellers has emerged, beyond paper pages. Let the bande play on…

Over the last one hundred years, Belgium has established its place in the pantheon of popular culture with its rich history of comic arts. Classic masters like Hergé (The Adventures of Tintin), Peyo (The Smurfs), Morris (Lucky Luke), and Philippe Geluck (Le Chat) exported Belgian wit and awareness to a global audience. The clear line style pioneered by Hergé ushered in an illustrative style that influenced generations of cartoonists. In the digital age, traditional readership has scattered and declined due to a lower subscription rate and daily routines that no longer involve sitting down at breakfast and reading paper newspapers, with their comic strips and Sunday ‘funnies.’ Despite this, the oldies are still formidable cash cows, as is evident by Hollywood productions in the last decade of several Smurf films and a 3d-animated feature of Tintin directed by Steven Spielberg.

If history is what you seek, what better way than spending an afternoon at the Belgian Comic Strip Center. The museum is dedicated to masters of the medium opened in 1989, and is housed in an exceptional Art Nouveau building designed by Victor Horta. What began modestly has grown into a major Brussels attraction.

With over 700 comic creators and illustrators living in the country, Belgium still maintains the highest density of graphic artists in the world. Students continue flocking to renowned programs in fine art, typography, graphic and visual communication at institutions such as Sint-Lucas School of Art in Ghent and Brussels’ National School of Visual Arts (ENSAV) at La Cambre. Founded in 1927 by the architect and designer Henry van de Velde, the old abbey that is now La Cambre demonstrates the reverence for bandes dessinées. ‘The Ninth Art,’ as the locals call it, has necessarily evolved in the 21st century.

Regardless of whether they ever attain the fame of their predecessors, a new crop of Belgian cartoonists has emerged. There are young award-winning storytellers such as Shamisa Debroey and Brecht Evens, who negate tradition while employing Jekyll and Hyde modes of illustration; and while editorial comics still have a say, the most cutting edge work being produced by graphic artists has migrated from print publication to temporal, experiential street art.

There was Remember Souvenir in 2017, the unforgettable Solvay building intervention by Denis Meyers, in which the artist filled all eight levels, wall-to-wall, ceiling-to-floor, with portraiture and text taken from his notebooks. Like most street art, there is an element of catharsis in the subversive act, which has found its way into the mainstream as well. Local venues such as Galerie Mazel place emphasis on urban artists, for example, Benjamin Sparks, Sonac, and Logan Hicks. In the Molière district there is Strokar Inside, a cross between a gallery and museum, and neither. Here the duo of Alexandra Lambert and Fred Atax has created a ‘supermarket for street art’ within the 5,000 m² condemned building. The space already attracts a host of international names and attractions in graffiti.

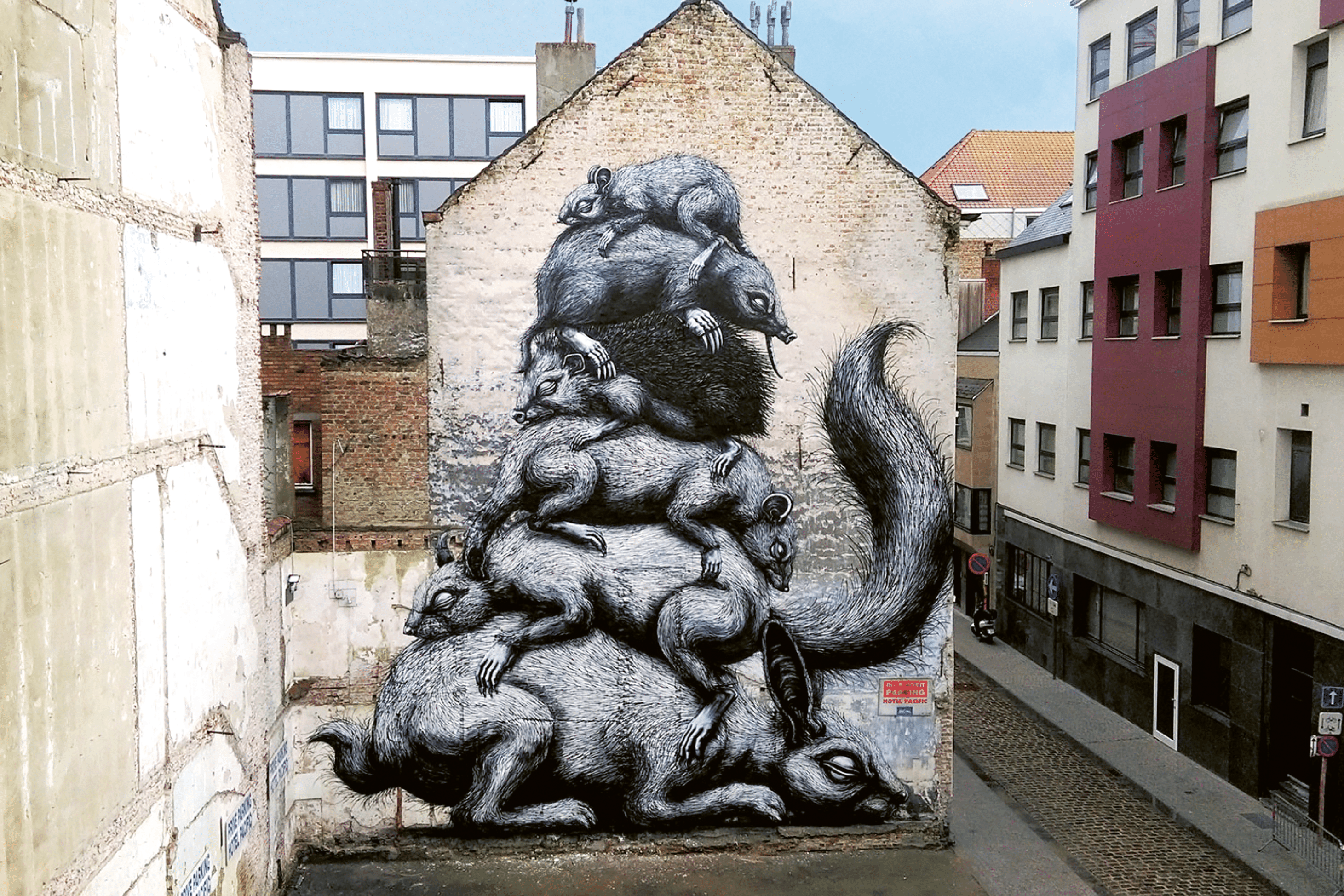

Major outdoor festivals catering to the form have also sprouted in the past five years all over Belgium, including Wall of Boho in Antwerp, Sorry Not Sorry in Ghent, and The Crystal Ship in the coastal town of Ostend. The works of local bombing legends like ROA, Iota, and PSO man can be found in these cities and beyond. Subsequently, nothing says you’ve made it like brand collaborations, such as Dzia with fashion label CKS and Joachim with the Italian shoe company Moaconcept.

Not to be left out, Belgium’s classic comic book tradition has also been honoured on outdoor building murals. One can pick up a map and follow the ‘BD parcours’ to see our heroes Boule & Bill or Billy the Cat animated on hidden corners and major intersections. By moving from the intimacy of paper to the exposed streets, where most of the new graphic art will inevitably get painted over or removed, this ‘neo-BD’ work eschews the hard recognition its predecessors had secured over a long period of time. Instead the new generation opts for a brief, ambitious moment of shared self-reflection that may very well live on eternally in the annals of social media. Or at the very least, as a future coffee table book.

Dossier

1 establishment, 3 trades

Face-à-face

Portrait

Behind the scenes

7th art